"I'm fascinated by the necessity of quick decisions," Inge Morath told me more than 30 years ago, when she came to NPR for an interview. Morath was in the business of quick decisions — as a photographer and photojournalist she was the first woman to be accepted as a full member of the Magnum photo agency.

Now, her life is the subject of a new biography by Linda Gordon. It recounts Morath's escape from Nazi Germany, her boundary-breaking career, and her marriage to playwright Arthur Miller.

Morath met Miller — and his then-wife Marilyn Monroe — in 1960 while she was taking publicity stills on the set of the film The Misfits. It was Monroe's last film, and Miller had written it for his wife.

"Inge took some very, very beautiful and sympathetic photographs of Marilyn Monroe," Gordon says. "But Miller had struck her as intensely interesting — and he was quite impressed," Gordon says.

Miller and Monroe's relationship had been on the rocks for some time. He and Morath had an affair and the two married in 1962. They were together for 40 years, until Inge's death in 2002.

In our 1987 interview, I asked Morath about whether she wished she'd paid more attention to Monroe, as Miller's first wife. In a marriage, "you have to be yourself," she said. "Even if you are the first, the second, or the third wife — if you try to take over anything, or imitate anything, I think it'd be a disaster."

"She was a woman of extraordinary self-confidence," says Gordon. "One sees that throughout her life ... self-confidence as a photographer, as a person, but also as her own sexual being."

Morath had a magnetic personality — and plenty of affairs.

"She was just a person who drew you in," says Gordon.

As a young woman, Morath had a rough time in Germany during the war.

"After Allied bombs started falling heavily on Berlin — and landing very near the munitions factory where she was a forced worker — she joined columns of hundreds, probably thousands, of people on foot just leaving Berlin," Gordon explains.

The biographer says Morath walked 455 miles to her parents in Salzburg, Austria. They were Nazi sympathizers — she was not. In Paris after the war, Morath got a job at Magnum, the elite photo agency founded by the great pioneers of photojournalism, Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson.

There, she did everything from secretarial work, to working with contact sheets, to cleaning the office, Gordon says, all the while honing her skills in photography. In 1955, she became Magnum's first full female member.

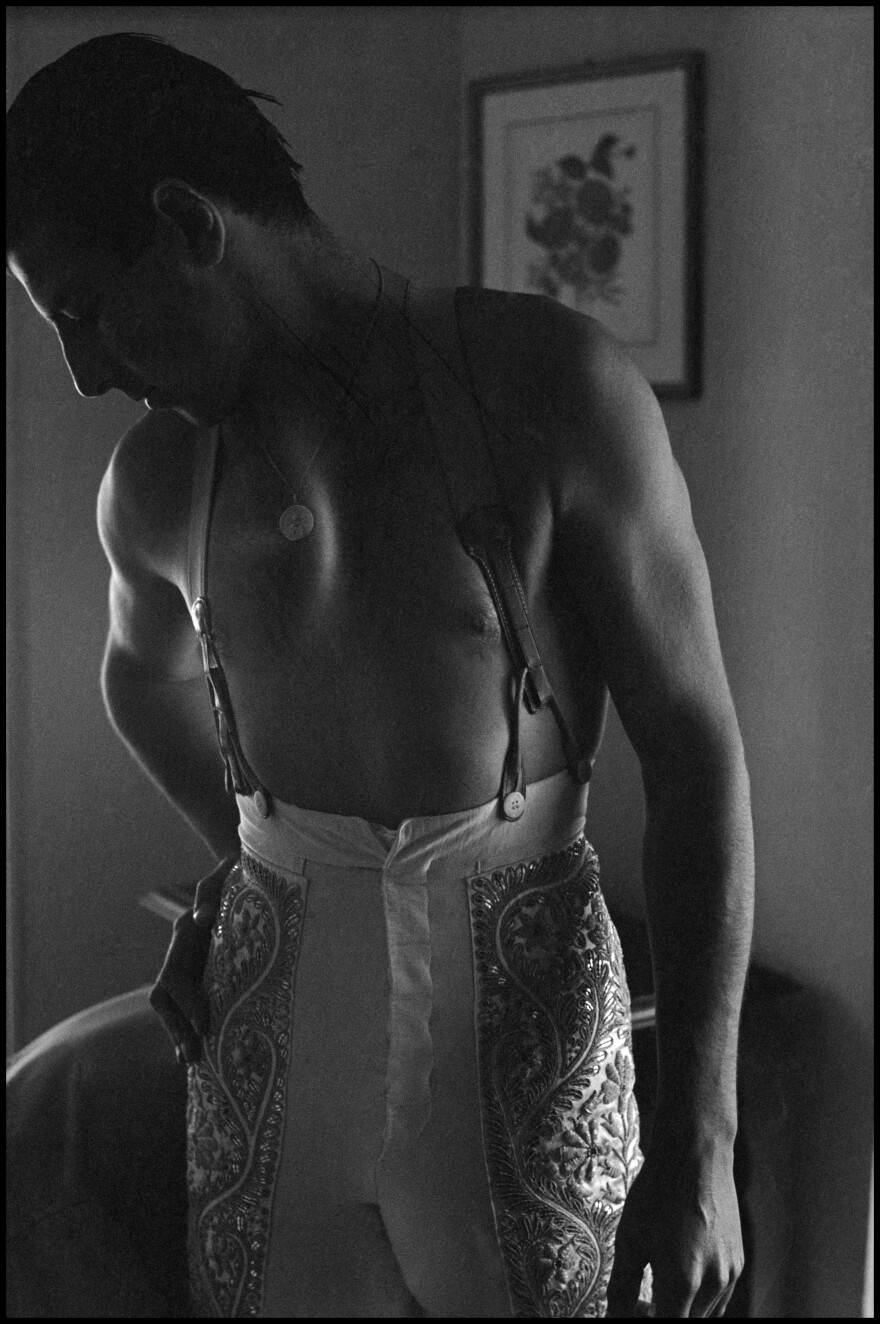

With her camera, Morath followed her passion for travel. In Spain, she wangled her way into the dressing room of the great toreador Antonio Ordóñez. Her 1954 photo shows him preparing for combat: his muscled chest is bare, and he's wearing skin-tight, sequin-embroidered pants.

It took chutzpah to get into his dressing room, where women were considered bad luck. "To get into that space she half jokingly made a completely outrageous argument," Gordon says. "She said, 'I'm wearing pants when I work, therefore I'm neither man nor woman.' "

In Seville, Morath put on a flamenco outfit and climbed up onto a chair to shoot dancers, whirling to the music in their layered red and white skirts and petticoats. "You only see these people from the waist down ..." Gordon says. "She has captured the movement — but with a camera just slow enough so that some of the picture is blurred as you see the skirts whirling around."

Outside of photography circles, Morath is known more for her marriage than for her work. "I do not like the fact that many people only know her as a wife of Arthur Miller — and, of course, the wife immediately after Marilyn Monroe — but my impression is that she was pretty copacetic about it," Gordon says.

There are trade-offs to familiarity, Morath told me in 1987. For example, when working on a portrait, she said she didn't necessarily want to meet her subject first.

There is a "wonderful element to a new meeting," she explained. Being strangers, the photographer and the subject are placed into a "sparring" position. "That's interesting," she said. "You kind of show more of yourself."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.