Part 1 of a four-part series

Somalia has not had an effective central government in two decades of civil war.

A new Cabinet took office in November in the capital, Mogadishu, and it's loaded with Somali-Americans. Some have given up quiet lives in the U.S. suburbs to try to turn around one of the world's most dangerous countries.

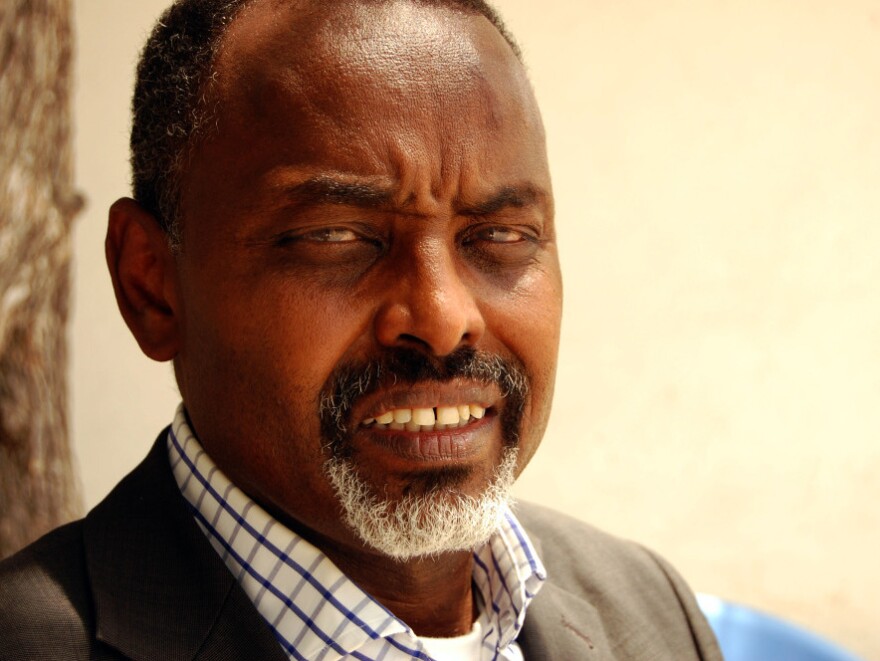

Abdulkareem Jama is the Somali transitional federal government minister of information, posts and telecommunications. He used to work in IT management for Congressional Quarterly Press. Jama grew up in Mogadishu before the war, when it was a beautiful seaside city.

Like many Somalis, he left, eventually settling in Northern Virginia. One day, Somali President Sheik Sharif Sheik Ahmed asked him to join Somalia's transitional government.

"I told my wife and she thought I was nuts," Jama says. But they talked it over and decided he should return and try to make a difference. Jama is one of eight Somali-Americans in the Cabinet of 19.

Their task is overwhelming.

Foreign Policy magazine puts Somalia at the top of its list of failed states. Transparency International calls it the most corrupt. Jama says the new government is trying to change that.

Ships arrive each day at the port of Mogadishu carrying cars, televisions and emergency food. But the port had never collected more than $900,000 a month in taxes because of graft. Jama says the government reshuffled the port administration and — voila — monthly revenue jumped to $ 2.5 million — a record.

But changing habits in Somalia is hard.

Jama says he recently received bids on a building renovation project for $2.6 million. "The gentleman told me this includes my cut," he says. "I said, 'OK, what exactly is that?' He said it's $1,080,000. You get 40 percent usually. I said, 'Wow.' "

Jama says the government will consider the bid — minus the kickback.

Moving to Mogadishu has turned Jama's life upside down. He used to live in a four-bedroom, red-brick colonial. Now, he sleeps in a walled compound guarded by soldiers with machine guns.

"Our view here is of the Indian Ocean, and when you open the window, you get a nice breeze," Jama says.

And the steady sound of mortar and rifle fire.

Two decades of violence has left Mogadishu in ruins. Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, the new prime minister, left in the 1980s. He returned last fall from the suburbs of Buffalo, where he worked for the New York State Department of Transportation.

"After 20 years of civil war, I could not recognize the areas that I grew up because of the destruction," Mohamed says. "My old house is where al-Shabab controls now."

Al-Shabab is a ruthless group of Islamist insurgents, who are affiliated with al-Qaida. They're trying to topple the government and create a strict Islamic state.

The main thing standing between the government and collapse is 8,000 African Union troops. But Mohamed says the government is making progress, building its own force to provide security.

"We mobilized our troops and boost their morale and pay salary, which has not happened before — and give them a sense of purpose," Mohamed says.

Government soldiers are accused of robbing people in the streets and selling ammunition to the enemy.

E.J. Hogendoorn, who works for the International Crisis Group, which monitors Somalia, says Mohamed and his Cabinet are the most technocratic the country has ever seen. But he says they lack the political skills to rally Mogadishu's various factions and effect real change.

"You need to have a constituency and you need to know your constituency quite well. And — I hate to say it — but if you've been living in Buffalo for 20 years, you're not going to have those contacts with people on the ground," Hogendoorn says.

Americans aren't the only ones returning to try to help Somalia. Mohamoud Nur, the mayor of Mogadishu, lived in London before he took this job five months ago.

Among other things, Nur has put in street lights, to encourage businesses to stay open after dark. Earlier this month, he tried to hold a cultural festival with singing and dancing. After so much carnage, he wanted to cheer people up.

But it didn't work out as he had planned.

A pickup truck with a machine gun on the back pulled up and opened fire on the crowd. Four people were killed and 16 more were wounded. The government arrested Mohamed Dhere, Mogadishu's former mayor, a powerful warlord and political spoiler.

Prime Minister Mohamed says this marks a new era of accountability.

"We're investigating who did what and definitely we will bring them to justice," he says.

It's also another test for a government that has little legitimacy with the people of Mogadishu. Somalia's government wasn't elected but created by a peace process, and its mandate ends in August.

Hogendoorn says unless it shows real progress by then, the United States should pull its support and look elsewhere for a solution to Somalia.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxNDQ2NDAxMDEyNzU2NzM2ODA3ZGI1ZA001))