Colorado’s rivers are known worldwide for their challenge and adventure for white river rafters and kayakers. Lyons, Colorado is far removed from the Olympic Games in London. But the inspiration for the 300-meter, manmade whitewater slalom course that’s front and center at the games this week can be traced back to the small town and a former Olympian.

41-year-old founder and president of S2o Design, Scott Shipley, says his love for kayaking and whitewater goes back to childhood.

“I always kind of liken it to when you’re a kid and you slide down a hill then you go back and you make toboggan run. And then you make it better and better and better,” he says. “I do that for kayaking. Only we get a lot of resources and we make it really good.”

…and Shipley knows what good is. He competed in three Olympics and won four world titles during his professional career as a kayaker.

So after earning a master’s degree in mechanical engineering from Georgia Tech he went from riding waves to sculpting them. At the Olympic level that means designing a manmade route that’s not subject to Colorado’s drought or London’s prolific rains.

“By having that pumped white water at the Olympic Games, you flip a switch and get exactly the whitewater you expect on the day of the event,” he says.

%22By%20having%20that%20pumped%20white%20water%20at%20the%20Olympic%20Games%2C%20you%20flip%20a%20switch%20and%20get%20exactly%20the%20whitewater%20you%20expect%20on%20the%20day%20of%20the%20event.%22

The Lee Valley White Water Centre north of London cost more than $48 million to construct and will be seen globally over four days of competition. Organizers hope that earning back that money will come from the course’s versatility—something other Olympic venues have struggled with in the past.

Since it was finished in December 2010, the Centre has been running commercial rafting trips. In recent weeks it’s been reconfigured to become a challenging slalom course.

RapidBlocs

The key to this versatility lies in Scott Shipley’s garage.

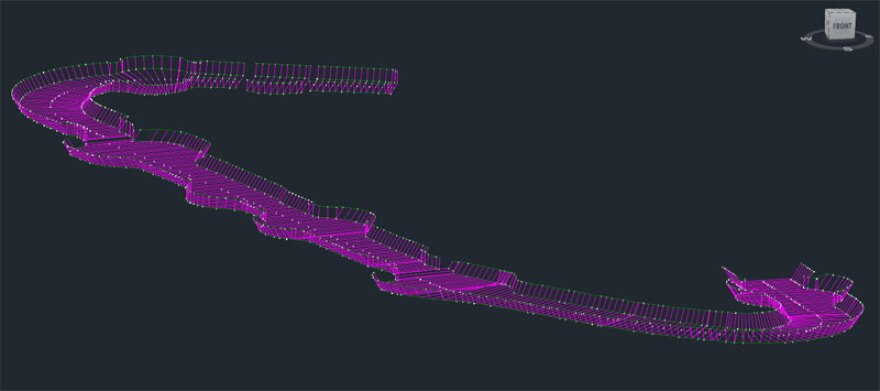

Shipley slides over a large, 30-pound, gray rectangle that looks a lot like a plastic cooler that you might take on a camping trip. He pops off the top to reveal metal rails that run from bottom to top inside what he calls the Rapidbloc.

“..and those connectors actually pass right through the block and pre stress it,” he says. “The reason we do that is plastic is weak in tension. If you pull on it, it tends to tear apart. But if you pull on metal rods, they do quite well.”

The blocks can be configured hooked together similar to Legos to form obstacles in the course's “C” shaped channel. The combinations can be tamer for rafting or extremely demanding for Olympic athletes

“In some ways the top guys love that. In other ways, people who are a notch down say that’s a really challenging course.”

So far the Olympic course has been described as “physically intense.” That’s for a sport where competitors already look extreme, bucking on whitewater waves like they’re riding a bronco as they move through 25 slalom gates. Silvan Poberaj is the head coach for the USA Canoe Kayak Slalom Team. He says there’s another thing he likes about this year’s route.

“This course is probably one of the best regarding the quality of eddies, they are all pretty fair,” he says.

This is Poberaj’s fifth Olympics coaching for the U.S. He says some venues in the past have been unfair because eddies—or circular movements of water—can act differently depending on when you’re riding down the course.

Varying currents can also cause problems.

“In some courses if the current goes sometimes to one side, another to another side, you cannot predict where it will push you,” he says. “That’s where we say it’s unfair—or less fair, less predictable.”

Fairness—and a nail biting whitewater ride—is what Shipley hopes athletes will remember most about the 2012 route.

“That’s something that’s never been brought to an Olympic design before. We’re right at the limit of what these paddlers can do the entire way down,” he says.

Shipley says Lee Valley White Water Centre can adjust that limit in the coming decades as top level athletes continue to improve. But whether or not they want a harder course is another question entirely.

They may just want to see how challenging it is first.